By James Okoth

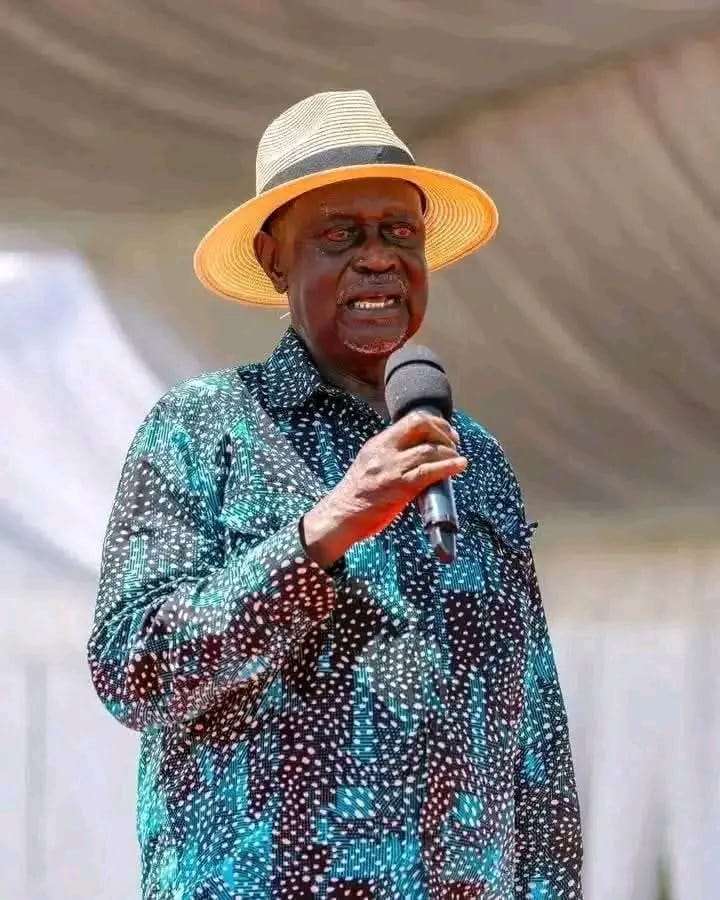

The long snaking road to Kang’o Ka Jaramogi has become a river of humanity. From dawn to dusk, they come in their thousands — villagers, students, politicians, clergy, foreign dignitaries — to pay homage at the fresh grave of Raila Amolo Odinga.

It is barely two weeks since his burial, yet the steady pilgrimage to his Bondo home already mirrors the devotion once reserved for saints or liberators. What began as mourning has quietly evolved into a cultural and national ritual — a return, a remembrance, a reaffirmation of the man whose political shadow loomed over Kenya for half a century.

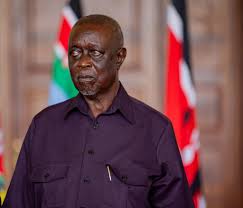

Raila was not made by the system. He fought it, challenged it, bent it to his will. From the cells of Nyayo House to the grand halls of the African Union, the Odinga name became synonymous with resilience.

“He was a man who lived for an idea, not an office,” said a mourner who had travelled from Meru County. “That is why even in death, he draws us here.”

Born into politics but never defined by inheritance, Raila carved his own political destiny. To his followers, he was Baba — the father of modern opposition politics, a master negotiator, an embodiment of Kenya’s democratic struggle. To his rivals, he was a formidable adversary who never stayed silent in the face of power.

From Washington to Addis Ababa, London to Johannesburg, messages of condolence flooded in. Leaders across the globe described him as “the bridge between Kenya’s past and future.” Yet at the core of his story lies something deeply Kenyan — a man who built his stature through grit, intellect, and endurance.

In Luo culture, death is not an end; it is a passage. Mourners return after burial to dance, sing, and celebrate the life of the departed — a rite known as tero buru. Raila’s funeral revived these fading traditions, blending state protocol with ancestral ritual.

In the days following his burial, Bondo has witnessed the essence of this cultural continuity. Bulls are driven around the homestead. Songs of liberation blend with Christian hymns. Visitors bow at the mound where the Enigma rests beside his father, Jaramogi Oginga Odinga — the father of opposition politics before him.

The return to Raila’s grave is not mere curiosity; it is the Luo way of reaffirming life after loss. It is, as one elder put it, “a covenant with our ancestors, that leadership never dies.”

Estimates from local administrators suggest that almost half a million people have already visited Raila’s resting place — an unprecedented figure in such a short time. The narrow village paths are jammed with vehicles bearing number plates from every corner of Kenya and beyond.

The government has quietly reinforced security, while the Odinga family insists the site remains a private homestead, not a shrine.

“Uhuru did not turn Raila’s grave into a shrine,” says a family source. “This is not political theatre. It is people honouring one of their own.”

Raila Odinga’s grave — simple and unadorned — stands as a symbol of humility amid grandeur. Around it, visitors light candles, drop flowers, whisper short prayers. They speak not to a ghost, but to a memory — of struggle, defiance, hope, unyielding faith in a better Kenya.

In the silence of Bondo’s evening wind, one feels the weight of history. The man who marched, was jailed, negotiated, and never stopped believing now rests where it all began. In a deeper sense, he has not left.

The people keep coming. The songs keep rising. The Enigma lives on — not in stone, but in the spirit of a nation still learning to rise from its own ashes.